Big man, Big Personality

Nick Molinaro had a question for his caller before the interview could begin.

“How did you find me?” the sports psychologist said with a chuckle from his office in Mendham, N.J.

Now 72, he is fresh off a turn at the PGA Championship in New York, where two of his clients, Bronson Burgoon and Tyler Hall, participated. He also advises the Rutgers University golf team and even has a client, rising senior John Felitto, on the golf team at Notre Dame.

This, however, would be the first time he’d ever answered a reporter’s questions about his namesake grandfather. Contrary to various published reports over the past century, the family patriarch did not perish in the 1919 Indy 500.

However, as the riding mechanic – or mechanician – for Arthur Thurman’s ill-fated Duesenberg, the elder Molinaro was severely injured in the Lap 45 accident. According to accounts, Molinaro was dragged under the car, suffered a fractured skull and was hospitalized after surgery.

His brother Michele, a professional boxer who fought under the name Mickey Delmont, reportedly traveled to Indianapolis to take Molinaro home to New Jersey after he recovered.

A native Texan turned Washington, D.C., lawyer, Thurman was driving in his first major race when the Thurman Special, the car he had designed and rebuilt himself, lost a wheel coming out of the backstretch at 90 mph. The car skidded, overturned and slammed into the inner wall; Thurman was thrown about 25 feet and died soon after being removed from the track.

The elder Molinaro, who died in the mid-1960s, later told his family Thurman had been decapitated.

“I don’t know if that’s true,” Molinaro’s grandson said. “I haven’t found this in any of the articles.”

An air of mystery has followed the elder Molinaro since the accident. News accounts that named him as “Molinero” or “Mollinard” were incorrect, his grandson said.

Nor was the riding mechanic “a Frenchman,” as another account claimed. In fact, Molinaro was a second-generation Italian- who was born in Newark, N.J.

The accident left Molinaro with a right eyelid that could not close on its own, effectively ending his career as a riding mechanic.

“He never wore a patch on it,” Molinaro’s grandson recalled. “I think he could still see out of it, so I don’t know it was neurological or whether there was a muscular piece that didn’t allow the eyelid to close. It was the strangest thing.”

The talented inventor and mechanic, who had worked eight years in the Duesenberg plant in Elizabethtown, N.J., later moved into aviation.

According to his namesake grandson, Molinaro spoke often of working on Charles Lindbergh’s “Spirit of St. Louis” before its historic Transatlantic flight. In fact, Molinaro told his family, he had carved the initials “NM” into the engine. Estranged from his family for decades, Molinaro lived for a time in the Midwest, his grandson said, and took the name Milton Wilcox in a nod to the

popular Howdy Wilcox after his death. Rachel Dormi, the mechanician’s estranged wife, told her three sons about Molinaro’s outsized personality.

“My father would reference my grandfather, who I guess was a real character,” Dr. Molinaro said. “He would find his way to where he wanted to be. He seemed to know a lot of people. He could charm anybody.”

That list included famed pilot Eddie Rickenbacker, who drove the pace car at the start of the 1919 race. The younger Molinaro remembers his grandfather mentioning Rickenbacker.

He also remembers the old mechanic’s physically imposing frame.

”He was a very big man,” Molinaro said. “I’m only 5-7, and my was dad was smaller than me, but my grandfather was probably 5-11. Certainly, back in that day, he was a big guy.”

Perhaps it was his physical strength that enabled him to survive the crash on Lap 45.

‘Wealthy mechanician’

Robert Bandini, the other riding mechanic involved in a deadly crash that day, would not be as fortunate.

The 21-year-old millionaire, heir to the Debaker estate in Southern California, would double as mechanic for the cars he often provided to well-known drivers such as Brent Harding and Roscoe Saarles. Bandini, a dedicated racing enthusiast, did this even though he may have been the wealthiest participant in the sport at the time.

At the 1919 Liberty Sweepstakes, Bandini was paired with 26-year-old driver Louis LeCocq when they hit the wall coming out of the southeast turn on Lap 97. According to reports, the Iowa-born LeCocq hit the sand and then the wall, causing the gas tank to explode.

LeCocq’s car finally stopped upside down, 75 feet from where it hit the wall, pinning both driver and mechanic underneath the vehicle.

“Covered with burning gas, their bodies flamed for five minutes before guards and spectators could put out the fire,” one account read. “They were burned beyond recognition, still strapped in their seats.”

LeCocq, one of the pre-race favorites, was driving Sarles’ self-dubbed Roamer (a Duesenberg) while Sarles drove Barney Oldfield’s car in the race.

Once the race resumed, drivers slowed down noticeably over the second half of the event. According to The New York Times account, average speed dipped from 91.3 over the first 275 miles to 87.1 over the remainder of the race.

In qualifying, drivers had reached 100 mph for the first time in race history.

LeCocq had worked as a mechanic on dirt tracks before becoming a driver in 1914 in Elgin, Ill. He had served as Eddie Hearne’s mechanic at IMS a few years before the accident that claimed his life in 1919.

“LeCocq and his wealthy mechanician are burned to death under flaming car – Thurman also loses life,” read the sub-headlines in The New York Times.

The danger aspect caused riding mechanics to be phased out at the Indy 500 from 1923-29 before returning for another eight years from 1930-37. That marked the last time they were used at the Brickyard.

“Back then, you had leather caps and no seat belts, no rearview mirrors,” Molinaro said. “It was part of the responsibility of the riding mechanic to give information. When you think about all the safety that’s come about since that time — a lot of safety in cars is based on what happens in Indy Racing.”

Need for speed

When Simon Pagenaud takes the green flag Sunday as the first Frenchman on the Indy 500 pole in a century, he will stir echoes of 1919 and countryman Rene Thomas, who finished 11th.

Nick Molinaro, grandson of the burly riding mechanic who survived the Thurman crash, will watch from his home in New Jersey and recall the man who died early in 1966, during Nick’s freshman year at the University of Scranton.

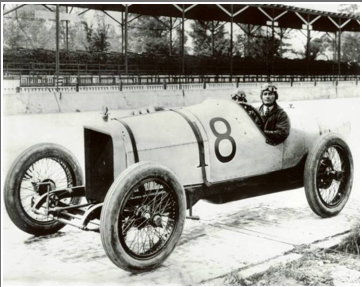

No 1919 race memorabilia items were handed down in the Molinaro family, although the mechanic’s grandson has purchased several vintage photographs of his grandfather from that time. One of them includes the 1919 Duesenberg Special by a photographer named John Conde; another shows the elder Molinaro on Daytona Beach that same year, but it has faded badly through the years.

Even though he learned some things about his mysterious grandfather over the final decade of his life, Dr. Molinaro still has so many unanswered questions.

“I would like to know what the experience was that led the car to go into the wall and what he could recall,” he said. “I’d like to know more about that. I’d like to know how he got into the racing piece.”

It was an accident of his own, while racing as an amateur at Lime Rock Park in Connecticut, that prompted Molinaro to switch specialties in his early 40s and become a sports psychologist. Three decades ago he owned a Porsche 911 and traveled to Sebring, Fla., to take racing lessons.

“I would say racing is in my blood,” he said. “I ride a motorcycle even now, at the age of 72. There’s a need for speed, absolutely.”

For Brian Wilcox and his family, the memories will center on the great-grandfather who remains a popular figure in Indy 500 history.

In addition to the former Nick Molinaro taking Wilcox as his last name, a 1930s-era racer named Howard Omar Wilcox went by Howdy Wilcox II despite there being no relation. Howard S. “Howdy” Wilcox, who served as director of personnel and public relations for The Star and The Indianapolis News and helped found the Little 500 bicycle race in Bloomington in 1951, probably didn’t appreciate the confusion over his father’s name.

After stopping by the speedway and visiting Howdy Wilcox’s gravesite at Crown Hill Cemetery, Brian Wilcox paused and considered what he would ask his famous great-grandfather if given the opportunity.

“Wow, that’s a good one,” he said. “What must it have been like to be embraced by so many of the wonderful fans in city of Indianapolis? Looking at it what it’s like now, I can only imagine what it would have been like 100 years ago to be embraced by the fans, to be loved by so many.”

Follow Mike Berardino on Twitter @MikeBerardino. His email is mberardino@gannett.com.

Nick Molinaro, 1919 Indy Riding Mechanic